1300 Foot Long Earthen Mound in Ohio Gotypes of Art Most Liekly Produced in the Northwest Coast

*The American Yawp is an evolving, collaborative text. Delight click hither to improve this affiliate.*

- I. Introduction

- 2. The First Americans

- III. European Expansion

- IV. Castilian Exploration and Conquest

- Five. Conclusion

- VI. Principal Sources

- Vii. Reference Material

I. Introduction

Europeans chosen the Americas "the New Earth." Simply for the millions of Native Americans they encountered, it was anything but. Humans have lived in the Americas for over ten thousand years. Dynamic and diverse, they spoke hundreds of languages and created thousands of distinct cultures. Native Americans built settled communities and followed seasonal migration patterns, maintained peace through alliances and warred with their neighbors, and adult self-sufficient economies and maintained vast merchandise networks. They cultivated distinct fine art forms and spiritual values. Kinship ties knit their communities together. Simply the inflow of Europeans and the resulting global substitution of people, animals, plants, and microbes—what scholars benignly call the Columbian Exchange—bridged more than 10 grand years of geographic separation, inaugurated centuries of violence, unleashed the greatest biological terror the world had ever seen, and revolutionized the history of the world. It began one of the well-nigh consequential developments in all of human history and the first chapter in the long American yawp.

II. The First Americans

American history begins with the first Americans. But where exercise their stories outset? Native Americans passed stories down through the millennia that tell of their cosmos and reveal the contours of Indigenous conventionalities. The Salinan people of present-day California, for example, tell of a bald hawkeye that formed the beginning man out of clay and the first woman out of a feather.1 According to a Lenape tradition, the world was made when Sky Woman cruel into a watery world and, with the assist of muskrat and beaver, landed safely on a turtle'due south back, thus creating Turtle Island, or North America. A Choctaw tradition locates southeastern peoples' beginnings inside the bully Mother Mound earthwork, Nunih Waya, in the lower Mississippi Valley.two Nahua people trace their ancestry to the place of the 7 Caves, from which their ancestors emerged before they migrated to what is now central Mexico.iii America'due south Indigenous peoples have passed down many accounts of their origins, written and oral, which share creation and migration histories.

Archaeologists and anthropologists, meanwhile, focus on migration histories. Studying artifacts, bones, and genetic signatures, these scholars have pieced together a narrative that claims that the Americas were in one case a "new world" for Native Americans besides.

The last global ice age trapped much of the earth's water in enormous continental glaciers. Twenty thousand years ago, ice sheets, some a mile thick, extended across Due north America as far south as modernistic-twenty-four hours Illinois. With and so much of the world's water captured in these massive water ice sheets, global sea levels were much lower, and a land bridge connected Asia and North America beyond the Bering Strait. Between twelve and twenty thousand years ago, Native ancestors crossed the ice, waters, and exposed lands between the continents of Asia and America. These mobile hunter-gatherers traveled in small-scale bands, exploiting vegetable, animate being, and marine resource into the Beringian tundra at the northwestern edge of North America. DNA evidence suggests that these ancestors paused—for perhaps fifteen yard years—in the expansive region between Asia and America.4 Other ancestors crossed the seas and voyaged along the Pacific coast, traveling along riverways and settling where local ecosystems permitted.5 Glacial sheets receded around 14 g years ago, opening a corridor to warmer climates and new resources. Some ancestral communities migrated south and e. Bear witness found at Monte Verde, a site in modern-twenty-four hours Chile, suggests that man activity began in that location at least 14,500 years ago. Similar evidence hints at human being settlement in the Florida panhandle and in Primal Texas at the same time.6 On many points, archaeological and traditional knowledge sources converge: the dental, archaeological, linguistic, oral, ecological, and genetic evidence illustrates a great deal of diverseness, with numerous groups settling and migrating over thousands of years, potentially from many different points of origin.7 Whether emerging from the earth, water, or sky; existence made by a creator; or migrating to their homelands, modern Native American communities recount histories in America that engagement long before homo memory.

In the Northwest, Native groups exploited the great salmon-filled rivers. On the plains and prairie lands, hunting communities followed bison herds and moved co-ordinate to seasonal patterns. In mountains, prairies, deserts, and forests, the cultures and ways of life of paleo-era ancestors were as varied as the geography. These groups spoke hundreds of languages and adopted singled-out cultural practices. Rich and diverse diets fueled massive population growth across the continent.

Agriculture arose sometime betwixt nine thousand and 5 thousand years ago, near simultaneously in the Eastern and Western Hemispheres. Mesoamericans in modern-day Mexico and Central America relied on domesticated maize (corn) to develop the hemisphere'due south kickoff settled population around 1200 BCE.8 Corn was high in caloric content, hands stale and stored, and, in Mesoamerica'south warm and fertile Gulf Coast, could sometimes be harvested twice in a twelvemonth. Corn—as well as other Mesoamerican crops—spread beyond Northward America and continues to hold an important spiritual and cultural place in many Native communities.

Prehistoric Settlement in Warren County, Mississippi. Mural by Robert Dafford, depicting the Kings Crossing archaeological site as it may have appeared in 1000 CE. Vicksburg Riverfront Murals.

Agriculture flourished in the fertile river valleys between the Mississippi River and the Atlantic Ocean, an area known as the Eastern Woodlands. There, 3 crops in particular—corn, beans, and squash, known as the Three Sisters—provided nutritional needs necessary to sustain cities and civilizations. In Woodland areas from the Swell Lakes and the Mississippi River to the Atlantic declension, Native communities managed their forest resources by called-for underbrush to create vast parklike hunting grounds and to clear the basis for planting the Three Sisters. Many groups used shifting tillage, in which farmers cut the forest, burned the undergrowth, then planted seeds in the food-rich ashes. When crop yields began to decline, farmers moved to another field and immune the land to recover and the woods to regrow before over again cutting the wood, burning the undergrowth, and restarting the cycle. This technique was particularly useful in areas with difficult soil. In the fertile regions of the Eastern Woodlands, Native American farmers engaged in permanent, intensive agriculture using mitt tools. The rich soil and use of hand tools enabled effective and sustainable farming practices, producing high yields without overburdening the soil.9 Typically in Woodland communities, women practiced agriculture while men hunted and fished.

Agronomics immune for dramatic social change, but for some, it also may take accompanied a turn down in health. Assay of remains reveals that societies transitioning to agronomics often experienced weaker basic and teeth.ten But despite these possible declines, agriculture brought important benefits. Farmers could produce more food than hunters, enabling some members of the community to pursue other skills. Religious leaders, skilled soldiers, and artists could devote their energy to activities other than nutrient production.

North America'due south Indigenous peoples shared some broad traits. Spiritual practices, understandings of belongings, and kinship networks differed markedly from European arrangements. Near Native Americans did non neatly distinguish betwixt the natural and the supernatural. Spiritual power permeated their world and was both tangible and accessible. It could be appealed to and harnessed. Kinship bound nigh Native North American people together. Near people lived in small communities tied by kinship networks. Many Native cultures understood ancestry as matrilineal: family unit and clan identity proceeded forth the female line, through mothers and daughters, rather than fathers and sons. Fathers, for instance, frequently joined mothers' extended families, and sometimes fifty-fifty a mother's brothers took a more than direct role in child-raising than biological fathers. Therefore, mothers ofttimes wielded enormous influence at local levels, and men's identities and influence often depended on their relationships to women. Native American culture, meanwhile, generally afforded greater sexual and marital freedom than European cultures.11 Women, for instance, ofttimes chose their husbands, and divorce oftentimes was a relatively elementary and straightforward process. Moreover, most Native peoples' notions of property rights differed markedly from those of Europeans. Native Americans generally felt a personal ownership of tools, weapons, or other items that were actively used, and this aforementioned rule applied to state and crops. Groups and individuals exploited particular pieces of land and used violence or negotiation to exclude others. But the right to the apply of land did not imply the right to its permanent possession.

Native Americans had many means of communicating, including graphic ones, and some of these artistic and chatty technologies are still used today. For example, Algonquian-speaking Ojibwes used birch-bark scrolls to tape medical treatments, recipes, songs, stories, and more. Other Eastern Woodland peoples wove plant fibers, embroidered skins with porcupine quills, and modeled the earth to make sites of circuitous ceremonial meaning. On the Plains, artisans wove buffalo pilus and painted on buffalo skins; in the Pacific Northwest, subsequently the inflow of Europeans, weavers wove goat hair into soft textiles with item patterns. Maya, Zapotec, and Nahua ancestors in Mesoamerica painted their histories on plant-derived textiles and carved them into stone. In the Andes, Inca recorders noted information in the course of knotted strings, or khipu.12

Two thousand years agone, some of the largest culture groups in North America were the Puebloan groups, centered in the electric current-day Greater Southwest (the southwestern United states of america and northwestern Mexico), the Mississippian groups located forth the Swell River and its tributaries, and the Mesoamerican groups of the areas now known equally cardinal Mexico and the Yucatán. Previous developments in agricultural technology enabled the explosive growth of the large early societies, such as that at Tenochtitlán in the Valley of United mexican states, Cahokia along the Mississippi River, and in the desert oasis areas of the Greater Southwest.

Native peoples in the Southwest began constructing these highly defensible cliff dwellings in 1190 CE and continued expanding and refurbishing them until 1260 CE before abandoning them effectually 1300 CE. Andreas F. Borchert, Mesa Verde National Park Cliff Palace. Wikimedia. Creative Eatables Attribution-Share Akin 3.0 Frg.

Chaco Canyon in northern New Mexico was habitation to ancestral Puebloan peoples betwixt 900 and 1300 CE. Every bit many as fifteen thousand individuals lived in the Chaco Canyon complex in nowadays-day New Mexico.13 Sophisticated agronomical practices, all-encompassing trading networks, and even the domestication of animals like turkeys allowed the population to swell. Massive residential structures, built from sandstone blocks and lumber carried across great distances, housed hundreds of Puebloan people. One building, Pueblo Bonito, stretched over two acres and rose five stories. Its half dozen hundred rooms were decorated with copper bells, turquoise decorations, and vivid macaws.xiv Homes like those at Pueblo Bonito included a pocket-sized dugout room, or kiva, which played an important role in a diversity of ceremonies and served equally an important center for Puebloan life and culture. Puebloan spirituality was tied both to the globe and the heavens, every bit generations carefully charted the stars and designed homes in line with the path of the lord's day and moon.15

The Puebloan people of Chaco Coulee faced several ecological challenges, including deforestation and overirrigation, which ultimately caused the community to collapse and its people to disperse to smaller settlements. An extreme fifty-year drought began in 1130. Soon thereafter, Chaco Canyon was deserted. New groups, including the Apache and Navajo, entered the vacated territory and adopted several Puebloan customs. The same drought that plagued the Pueblo too likely affected the Mississippian peoples of the American Midwest and South. The Mississippians adult i of the largest civilizations north of mod-day Mexico. Roughly i thou years agone, the largest Mississippian settlement, Cahokia, located just e of modernistic-24-hour interval St. Louis, peaked at a population of between ten thousand and thirty thousand. It rivaled gimmicky European cities in size. No city northward of mod Mexico, in fact, would match Cahokia's height population levels until later on the American Revolution. The city itself spanned 2 thousand acres and centered on Monks Mound, a large earthen hill that rose ten stories and was larger at its base of operations than the pyramids of Egypt. As with many of the peoples who lived in the Woodlands, life and death in Cahokia were linked to the movement of the stars, dominicus, and moon, and their ceremonial earthwork structures reflect these important structuring forces.

Cahokia was politically organized around chiefdoms, a hierarchical, clan-based arrangement that gave leaders both secular and sacred authority. The size of the urban center and the extent of its influence suggest that the city relied on a number of lesser chiefdoms nether the authority of a paramount leader. Social stratification was partly preserved through frequent warfare. State of war captives were enslaved, and these captives formed an important role of the economic system in the North American Southeast. Native American slavery was non based on holding people as property. Instead, Native Americans understood the enslaved as people who lacked kinship networks. Slavery, then, was not ever a permanent status. Very often, a formerly enslaved person could become a fully integrated member of the community. Adoption or matrimony could enable an enslaved person to enter a kinship network and join the community. Slavery and captive trading became an of import way that many Native communities regrew and gained or maintained power.

An artist'south rendering of Cahokia as it may have appeared in 1150 CE. Prepared past Bill Isminger and Marker Esarey with artwork by Greg Harlin. From the Cahokia Mounds Land Historic Site.

Around 1050, Cahokia experienced what one archeologist has called a "big bang," which included "a near instantaneous and pervasive shift in all things political, social, and ideological."16 The population grew nigh 500 percent in only one generation, and new people groups were absorbed into the city and its supporting communities. Past 1300, the once-powerful city had undergone a series of strains that led to collapse. Scholars previously pointed to ecological disaster or irksome depopulation through emigration, but new research instead emphasizes mounting warfare, or internal political tensions. Ecology explanations suggest that population growth placed too dandy a burden on the arable land. Others suggest that the demand for fuel and building materials led to deforestation, erosion, and perhaps an extended drought. Recent evidence, including defensive stockades, suggests that political turmoil amongst the ruling elite and threats from external enemies may explain the terminate of the in one case-great civilization.17

North American communities were connected past kin, politics, and culture and sustained by long-altitude trading routes. The Mississippi River served equally an important trade artery, but all of the continent's waterways were vital to transportation and advice. Cahokia became a key trading centre partly considering of its position near the Mississippi, Illinois, and Missouri Rivers. These rivers created networks that stretched from the Great Lakes to the American Southeast. Archaeologists can place materials, similar seashells, that traveled over a thousand miles to reach the middle of this civilization. At to the lowest degree 3,500 years ago, the community at what is now Poverty Point, Louisiana, had access to copper from present-day Canada and flintstone from mod-day Indiana. Sheets of mica found at the sacred Serpent Mound site near the Ohio River came from the Allegheny Mountains, and obsidian from nearby earthworks came from Mexico. Turquoise from the Greater Southwest was used at Teotihuacan 1200 years ago.

In the Eastern Woodlands, many Native American societies lived in smaller, dispersed communities to accept advantage of rich soils and abundant rivers and streams. The Lenapes, also known as Delawares, farmed the bottomlands throughout the Hudson and Delaware River watersheds in New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware. Their hundreds of settlements, stretching from southern Massachusetts through Delaware, were loosely bound together by political, social, and spiritual connections.

Dispersed and relatively independent, Lenape communities were jump together by oral histories, ceremonial traditions, consensus-based political organization, kinship networks, and a shared clan arrangement. Kinship tied the various Lenape communities and clans together, and social club was organized along matrilineal lines. Marriage occurred between clans, and a married man joined the clan of his wife. Lenape women wielded authority over marriages, households, and agricultural production and may even have played a significant part in determining the choice of leaders, chosen sachems. Dispersed authority, pocket-size settlements, and kin-based organization contributed to the long-lasting stability and resilience of Lenape communities.xviii One or more than sachems governed Lenape communities past the consent of their people. Lenape sachems acquired their say-so by demonstrating wisdom and experience. This differed from the hierarchical organization of many Mississippian cultures. Large gatherings did exist, withal, as dispersed communities and their leaders gathered for ceremonial purposes or to make big decisions. Sachems spoke for their people in larger councils that included men, women, and elders. The Lenapes experienced occasional tensions with other Indigenous groups like the Iroquois to the northward or the Susquehannock to the south, but the lack of defensive fortifications near Lenape communities convinced archaeologists that the Lenapes avoided large-scale warfare.

The continued longevity of Lenape societies, which began centuries earlier European contact, was too due to their skills equally farmers and fishers. Along with the Iii Sisters, Lenape women planted tobacco, sunflowers, and gourds. They harvested fruits and basics from copse and cultivated numerous medicinal plants, which they used with cracking proficiency. The Lenapes organized their communities to take advantage of growing seasons and the migration patterns of animals and fowl that were a office of their diet. During planting and harvesting seasons, Lenapes gathered in larger groups to coordinate their labor and accept advantage of local abundance. Equally proficient fishers, they organized seasonal fish camps to net shellfish and catch shad. Lenapes wove nets, baskets, mats, and a variety of household materials from the rushes establish along the streams, rivers, and coasts. They made their homes in some of the nigh fertile and arable lands in the Eastern Woodlands and used their skills to create a stable and prosperous civilisation. The start Dutch and Swedish settlers who encountered the Lenapes in the seventeenth century recognized Lenape prosperity and quickly sought their friendship. Their lives came to depend on it.

In the Pacific Northwest, the Kwakwaka'wakw, Tlingits, Haidas, and hundreds of other peoples, speaking dozens of languages, thrived in a state with a moderate climate, lush forests, and many rivers. The peoples of this region depended on salmon for survival and valued information technology appropriately. Images of salmon decorated totem poles, baskets, canoes, oars, and other tools. The fish was treated with spiritual respect and its image represented prosperity, life, and renewal. Sustainable harvesting practices ensured the survival of salmon populations. The Coast Salish people and several others celebrated the Showtime Salmon Ceremony when the starting time migrating salmon was spotted each season. Elders closely observed the size of the salmon run and delayed harvesting to ensure that a sufficient number survived to spawn and return in the future.xix Men ordinarily used nets, hooks, and other small tools to capture salmon as they migrated upriver to spawn. Massive cedar canoes, as long as fifty feet and carrying equally many as twenty men, too enabled extensive fishing expeditions in the Pacific Sea, where skilled fishermen caught halibut, sturgeon, and other fish, sometimes hauling thousands of pounds in a single canoe.xx

Food surpluses enabled pregnant population growth, and the Pacific Northwest became one of the nearly densely populated regions of North America. The combination of population density and surplus food created a unique social system centered on elaborate feasts, called potlatches. These potlatches celebrated births and weddings and adamant social status. The party lasted for days and hosts demonstrated their wealth and ability by entertaining guests with food, artwork, and performances. The more the hosts gave away, the more prestige and power they had within the group. Some men saved for decades to host an improvident potlatch that would in plow give him greater respect and ability within the customs.

Intricately carved masks, similar the Crooked Nib of Sky Mask, used natural elements such equally animals to represent supernatural forces during ceremonial dances and festivals. Nineteenth-century crooked beak of heaven mask from the Kwakwaka'wakw. Wikimedia. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported.

Many peoples of the Pacific Northwest built elaborate plank houses out of the region's arable cedar trees. The five-hundred-foot-long Suquamish Oleman House (or Quondam Homo Business firm), for example, rested on the banks of Puget Sound.21 Giant cedar copse were also carved and painted in the shape of animals or other figures to tell stories and express identities. These totem poles became the most recognizable creative form of the Pacific Northwest, but people also carved masks and other wooden items, such as hand drums and rattles, out of the region's great trees.

Despite commonalities, Native cultures varied greatly. The New World was marked by diversity and contrast. By the time Europeans were poised to cantankerous the Atlantic, Native Americans spoke hundreds of languages and lived in keeping with the hemisphere's many climates. Some lived in cities, others in small bands. Some migrated seasonally; others settled permanently. All Native peoples had long histories and well-formed, unique cultures that developed over millennia. But the arrival of Europeans inverse everything.

Iii. European Expansion

Scandinavian seafarers reached the New Globe long earlier Columbus. At their peak they sailed every bit far due east as Constantinople and raided settlements as far due south equally North Africa. They established limited colonies in Iceland and Greenland and, effectually the year 1000, Leif Erikson reached Newfoundland in present-twenty-four hour period Canada. Merely the Norse colony failed. Culturally and geographically isolated, the Norse were driven back to the ocean by some combination of limited resources, inhospitable weather, nutrient shortages, and Native resistance.

Then, centuries before Columbus, the Crusades linked Europe with the wealth, power, and knowledge of Asia. Europeans rediscovered or adopted Greek, Roman, and Muslim knowledge. The hemispheric dissemination of appurtenances and knowledge not but sparked the Renaissance just fueled long-term European expansion. Asian goods flooded European markets, creating a need for new commodities. This trade created vast new wealth, and Europeans battled one another for trade supremacy.

European nation-states consolidated under the authority of powerful kings. A series of military conflicts betwixt England and France—the Hundred Years' War—accelerated nationalism and cultivated the financial and armed forces administration necessary to maintain nation-states. In Kingdom of spain, the marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile consolidated the two about powerful kingdoms of the Iberian peninsula. The Crusades had never ended in Iberia: the Spanish crown concluded centuries of intermittent warfare—the Reconquista—by expelling Muslim Moors and Iberian Jews from the Iberian peninsula in 1492, just as Christopher Columbus sailed west. With new ability, these new nations—and their newly empowered monarchs—yearned to admission the wealth of Asia.

Seafaring Italian traders commanded the Mediterranean and controlled trade with Asia. Kingdom of spain and Portugal, at the edges of Europe, relied on middlemen and paid higher prices for Asian goods. They sought a more direct road. And so they looked to the Atlantic. Portugal invested heavily in exploration. From his estate on the Sagres Peninsula of Portugal, a rich sailing port, Prince Henry the Navigator (Infante Henry, Knuckles of Viseu) invested in research and technology and underwrote many technological breakthroughs. His investments bore fruit. In the fifteenth century, Portuguese sailors perfected the astrolabe, a tool to calculate latitude, and the caravel, a ship well suited for body of water exploration. Both were technological breakthroughs. The astrolabe allowed for precise navigation, and the caravel, dissimilar more common vessels designed for trading on the relatively placid Mediterranean, was a rugged send with a deep draft capable of making lengthy voyages on the open up ocean and, equally of import, conveying large amounts of cargo while doing so.

Engraving of sixteenth-century Lisbon from Civitatis Orbis Terrarum, "The Cities of the World," ed. Georg Braun (Cologne: 1572). Wikimedia.

Blending economic and religious motivations, the Portuguese established forts along the Atlantic coast of Africa during the fifteenth century, inaugurating centuries of European colonization there. Portuguese trading posts generated new profits that funded further merchandise and farther colonization. Trading posts spread beyond the vast coastline of Africa, and by the terminate of the fifteenth century, Vasco da Gama leapfrogged his way around the coasts of Africa to attain India and other lucrative Asian markets.

The vagaries of ocean currents and the limits of contemporary technology forced Iberian sailors to sail w into the open sea before cutting back east to Africa. So doing, the Spanish and Portuguese stumbled on several islands off the declension of Europe and Africa, including the Azores, the Canary Islands, and the Republic of cape verde Islands. They became grooming grounds for the afterward colonization of the Americas and saw the beginning big-scale cultivation of saccharide by enslaved laborers.

Carbohydrate was originally grown in Asia but became a popular, widely assisting luxury item consumed by the nobility of Europe. The Portuguese learned the sugar-growing procedure from Mediterranean plantations started by Muslims, using imported enslaved labor from southern Russia and Islamic countries. Sugar was a difficult ingather. Information technology required tropical temperatures, daily rainfall, unique soil weather condition, and a fourteen-month growing season. But on the newly discovered, by and large uninhabited Atlantic islands, the Portuguese had plant new, defensible country to back up sugar product. New patterns of homo and ecological destruction followed. Isolated from the mainlands of Europe and Africa for millennia, Canary Island natives—known as the Guanches—were enslaved or perished before long after Europeans arrived. This demographic disaster presaged the demographic results for the Native American populations upon the inflow of the Spanish.

Portugal'southward would-exist planters needed workers to cultivate the hard, labor-intensive ingather. They first turned to the trade relationships that Portuguese merchants established with African city-states in Senegambia, along the Gold Declension, equally well as the kingdoms of Benin, Kongo, and Ndongo.22 The Portuguese turned to enslaved Africans from the mainland as a labor source for these isle plantations. At the outset of this Euroafrican slave-trading system, African leaders traded war captives—who by custom forfeited their freedom if captured during battle—for Portuguese guns, iron, and manufactured appurtenances. It is important to note that slaving in Africa, like slaving amongst Indigenous Americans, bore little resemblance to the chattel slavery of the antebellum United States.23

From bases along the Atlantic coast, the Portuguese began purchasing enslaved people for consign to the Atlantic islands of Madeira, the Canaries, and the Cape Verdes to work the saccharide fields. Thus, were born the first great Atlantic plantations. A few decades later, at the end of the 15thursday century, the Portuguese plantation arrangement developed on the island of São Tomé became a model for the plantation arrangement as it was expanded across the Atlantic.

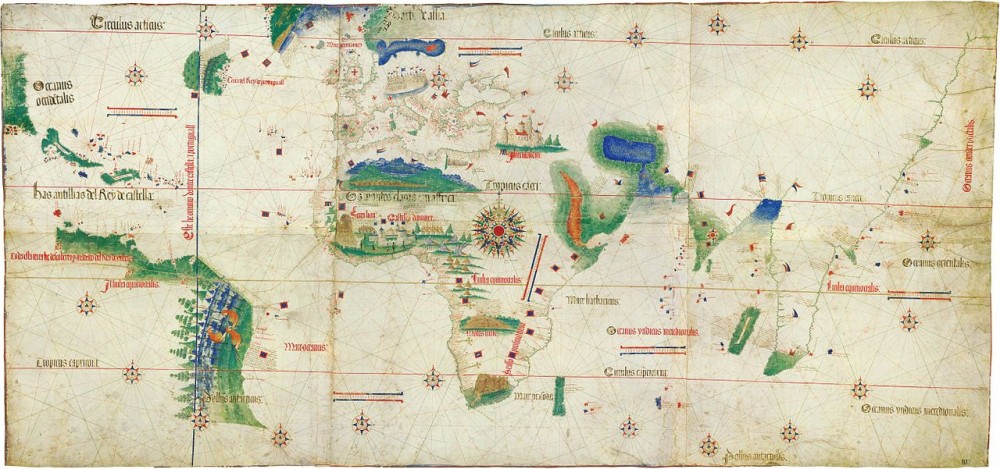

Past the fifteenth century, the Portuguese had established forts and colonies on islands and along the rim of the Atlantic Ocean; other major European countries soon followed in step. An anonymous cartographer created this map known as the Cantino Map, the earliest known map of European exploration in the New World, to depict these holdings and argue for the greatness of his native Portugal. Cantino planisphere (1502), Biblioteca Estense, Modena, Italy. Wikimedia.

Spain, too, stood on the cutting edge of maritime technology. Spanish sailors had become masters of the caravels. As Portugal consolidated control over African trading networks and the circuitous eastbound bounding main route to Asia, Spain yearned for its ain path to empire. Christopher Columbus, a skilled Italian-born crewman who had studied under Portuguese navigators, promised just that opportunity.

Educated Asians and Europeans of the fifteenth century knew the world was round. They too knew that while it was therefore technically possible to achieve Asia by sailing w from Europe—thereby avoiding Italian or Portuguese middlemen—the globe's vast size would doom even the greatest caravels to starvation and thirst long before they always reached their destination. But Columbus underestimated the size of the globe by a full two thirds and therefore believed information technology was possible. After unsuccessfully shopping his proposed expedition in several European courts, he convinced Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand of Kingdom of spain to provide him three pocket-size ships, which set canvas in 1492. Columbus was both confoundingly wrong about the size of the earth and spectacularly lucky that ii large continents lurked in his path. On October 12, 1492, later on 2 months at sea, the Niña, Pinta, and Santa María and their xc men landed in the modern-24-hour interval Bahamas.

The Indigenous Arawaks, or Taíno, populated the Caribbean islands. They fished and grew corn, yams, and cassava. Columbus described them every bit innocents. "They are very gentle and without noesis of what is evil; nor the sins of murder or theft," he reported to the Castilian crown. "Your highness may believe that in all the world there tin exist no improve people. . . . They beloved their neighbors as themselves, and their oral communication is the sweetest and gentlest in the world, and always with a grin." But Columbus had come for wealth and he could find petty. The Arawaks, however, wore pocket-sized gold ornaments. Columbus left 30-9 Spaniards at a armed services fort on Hispaniola to find and secure the source of the gold while he returned to Spain, with a dozen captured and branded Arawaks. Columbus arrived to peachy acclaim and quickly worked to outfit a render voyage. Spain's New Globe motives were clear from the beginning. If outfitted for a return voyage, Columbus promised the Castilian crown gold and enslaved laborers. Columbus reported, "With fifty men they can all be subjugated and fabricated to practise what is required of them."24

Columbus was outfitted with seventeen ships and over one thousand men to return to the West Indies (Columbus made four voyages to the New Globe). Still believing he had landed in the East Indies, he promised to reward Isabella and Ferdinand'southward investment. But when fabric wealth proved slow in coming, the Spanish embarked on a roughshod campaign to excerpt every possible ounce of wealth from the Caribbean. The Spanish decimated the Arawaks. Bartolomé de Las Casas traveled to the New World in 1502 and later wrote, "I saw with these Optics of mine the Spaniards for no other reason, but merely to gratify their encarmine mindedness, cutting off the Hands, Noses, and Ears, both of Indians and Indianesses."25 When the enslaved laborers wearied the islands' meager gold reserves, the Spaniards forced them to labor on their huge new estates, the encomiendas. Las Casas described European barbarities in roughshod detail. Past presuming the natives had no humanity, the Spaniards utterly abased theirs. Casual violence and dehumanizing exploitation ravaged the Arawaks. The Indigenous population collapsed. Within a few generations the whole island of Hispaniola had been depopulated and a whole people exterminated. Historians' estimates of the island's pre-contact population range from fewer than one one thousand thousand to as many as eight million (Las Casas estimated it at three 1000000). In a few short years, they were gone. "Who in futurity generations will believe this?" Las Casas wondered. "I myself writing it as a knowledgeable bystander can hardly believe it."

Despite the variety of Native populations and the existence of several potent empires, Native Americans were wholly unprepared for the arrival of Europeans. Biology magnified European cruelties. Cut off from the Onetime World, its domesticated animals, and its immunological history, Native Americans lived free from the terrible diseases that ravaged populations in Asia, Europe and Africa. But their blessing now became a curse. Native Americans lacked the immunities that Europeans and Africans had adult over centuries of deadly epidemics, and so when Europeans arrived, carrying smallpox, typhus, influenza, diphtheria, measles, and hepatitis, plagues decimated Native communities.26 Many died in war and slavery, but millions died in epidemics. All told, in fact, some scholars estimate that as much every bit 90 percent of the population of the Americas perished within the kickoff century and a one-half of European contact.27

Though ravaged past disease and warfare, Native Americans forged middle grounds, resisted with violence, accommodated and adjusted to the challenges of colonialism, and continued to shape the patterns of life throughout the New World for hundreds of years. Simply the Europeans kept coming.

Four. Spanish Exploration and Conquest

As news of the Spanish conquest spread, wealth-hungry Spaniards poured into the New Earth seeking land, gold, and titles. A New World empire spread from Espana's Caribbean foothold. Motives were plain: said ane soldier, "nosotros came here to serve God and the rex, and also to go rich."28 Mercenaries joined the conquest and raced to capture the human and material wealth of the New World.

The Spanish managed labor relations through a legal organization known as the encomienda, an exploitive feudal system in which Spain tied Indigenous laborers to vast estates. In the encomienda, the Spanish crown granted a person not only land merely a specified number of natives as well. Encomenderos brutalized their laborers. Subsequently Bartolomé de Las Casas published his incendiary account of Castilian abuses (The Destruction of the Indies), Spanish regime abolished the encomienda in 1542 and replaced it with the repartimiento. Intended every bit a milder organization, the repartimiento however replicated many of the abuses of the older system, and the rapacious exploitation of the Native population continued every bit Espana spread its empire over the Americas.

El Castillo (pyramid of Kukulcán) in Chichén Itzá. Photograph past Daniel Schwen. Wikimedia. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike iv.0 International.

Equally Kingdom of spain's New World empire expanded, Spanish conquerors met the massive empires of Central and South America, civilizations that dwarfed anything plant in North America. In Primal America the Maya built massive temples, sustained large populations, and synthetic a complex and long-lasting civilisation with a written linguistic communication, advanced mathematics, and stunningly accurate calendars. But Maya civilization, although it had not disappeared, withal complanate before European arrival, likely because of droughts and unsustainable agricultural practices. Only the eclipse of the Maya only heralded the later rise of the about powerful Native civilization e'er seen in the Western Hemisphere: the Aztecs.

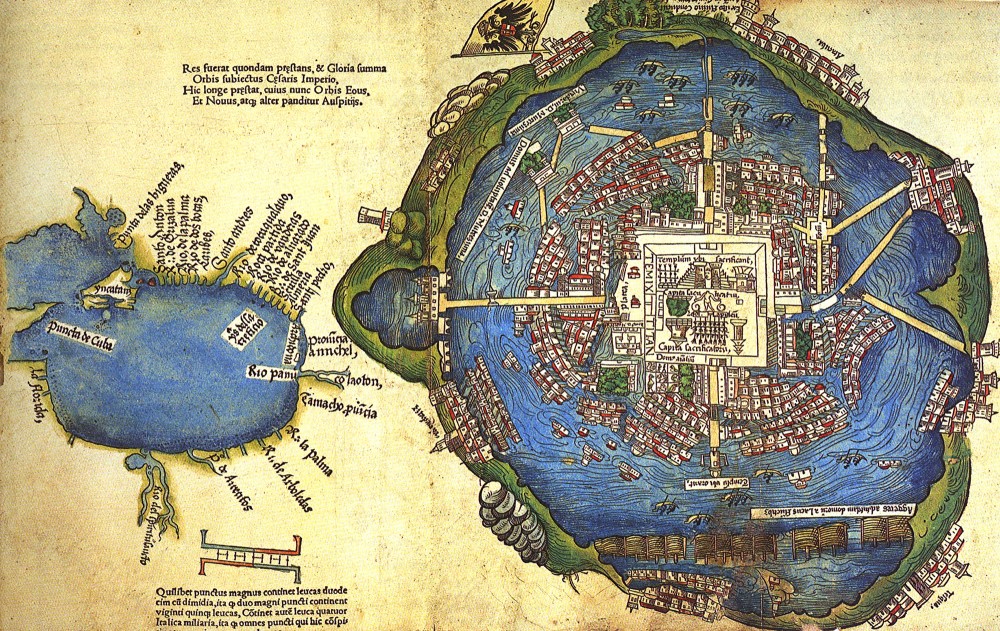

Militaristic migrants from northern Mexico, the Aztecs moved due south into the Valley of Mexico, conquered their way to say-so, and congenital the largest empire in the New Earth. When the Spaniards arrived in United mexican states they found a sprawling civilization centered around Tenochtitlán, an awe-inspiring city built on a series of natural and homo-fabricated islands in the middle of Lake Texcoco, located today within modern-twenty-four hour period Mexico City. Tenochtitlán, founded in 1325, rivaled the earth's largest cities in size and grandeur.29

Much of the urban center was built on large artificial islands called chinampas, which the Aztecs constructed by dredging mud and rich sediment from the bottom of the lake and depositing it over time to form new landscapes. A massive pyramid temple, the Templo Mayor, was located at the city center (its ruins tin can however be found in the center of Mexico Metropolis). When the Spaniards arrived, they could scarcely believe what they saw: 70,000 buildings, housing perhaps 200,000–250,000 people, all built on a lake and connected by causeways and canals. Bernal Díaz del Castillo, a Spanish soldier, later recalled, "When nosotros saw then many cities and villages built in the water and other great towns on dry country, we were amazed and said that it was like the enchantments. . . . Some of our soldiers fifty-fifty asked whether the things that we saw were not a dream? . . . I do not know how to depict it, seeing things as nosotros did that had never been heard of or seen before, not even dreamed about."30

From their isle city the Aztecs dominated an enormous swath of key and southern Mesoamerica. They ruled their empire through a decentralized network of subject peoples that paid regular tribute—including everything from the well-nigh basic items, such as corn, beans, and other foodstuffs, to luxury goods such equally jade, cacao, and golden—and provided troops for the empire. But unrest festered beneath the Aztecs' purple power, and European conquerors lusted later its vast wealth.

This sixteenth-century map of Tenochtitlan shows the aesthetic beauty and advanced infrastructure of this cracking Aztec urban center. Map, c. 1524, Wikimedia.

Hernán Cortés, an ambitious, thirty-four-year-old Spaniard who had won riches in the conquest of Cuba, organized an invasion of Mexico in 1519. Sailing with six hundred men, horses, and cannon, he landed on the coast of United mexican states. Relying on a Native translator, whom he called Doña Marina, and whom Mexican folklore denounces as La Malinche, Cortés gathered information and allies in training for conquest. Through intrigue, brutality, and the exploitation of endemic political divisions, he enlisted the aid of thousands of Native allies, defeated Spanish rivals, and marched on Tenochtitlán.

Aztec authorization rested on fragile foundations and many of the region's semi-independent city-states yearned to break from Aztec rule. Nearby kingdoms, including the Tarascans to the due north and the remains of Maya city-states on the Yucatán peninsula, chafed at Aztec power.

Through persuasion, the Spaniards entered Tenochtitlán peacefully. Cortés then captured the emperor Montezuma and used him to gain command of the Aztecs' gold and silver reserves and their network of mines. Eventually, the Aztecs revolted. Montezuma was branded a traitor, and uprising ignited the city. Montezuma was killed along with a third of Cortés's men in la noche triste, the "nighttime of sorrows." The Spanish fought through thousands of Indigenous insurgents and across canals to abscond the metropolis, where they regrouped, enlisted more Native allies, captured Castilian reinforcements, and, in 1521, besieged the island city. The Spaniards' eighty-five-day siege cutting off nutrient and fresh water. Smallpox ravaged the city. 1 Spanish observer said it "spread over the people equally great destruction. Some it covered on all parts—their faces, their heads, their breasts, and so on. At that place was great havoc. Very many died of information technology. . . . They could non move; they could non stir."31 Cortés, the Spaniards, and their Native allies so sacked the city. The temples were plundered and fifteen thousand died. After two years of disharmonize, a million-person-stiff empire was toppled by illness, dissension, and a thousand European conquerors.

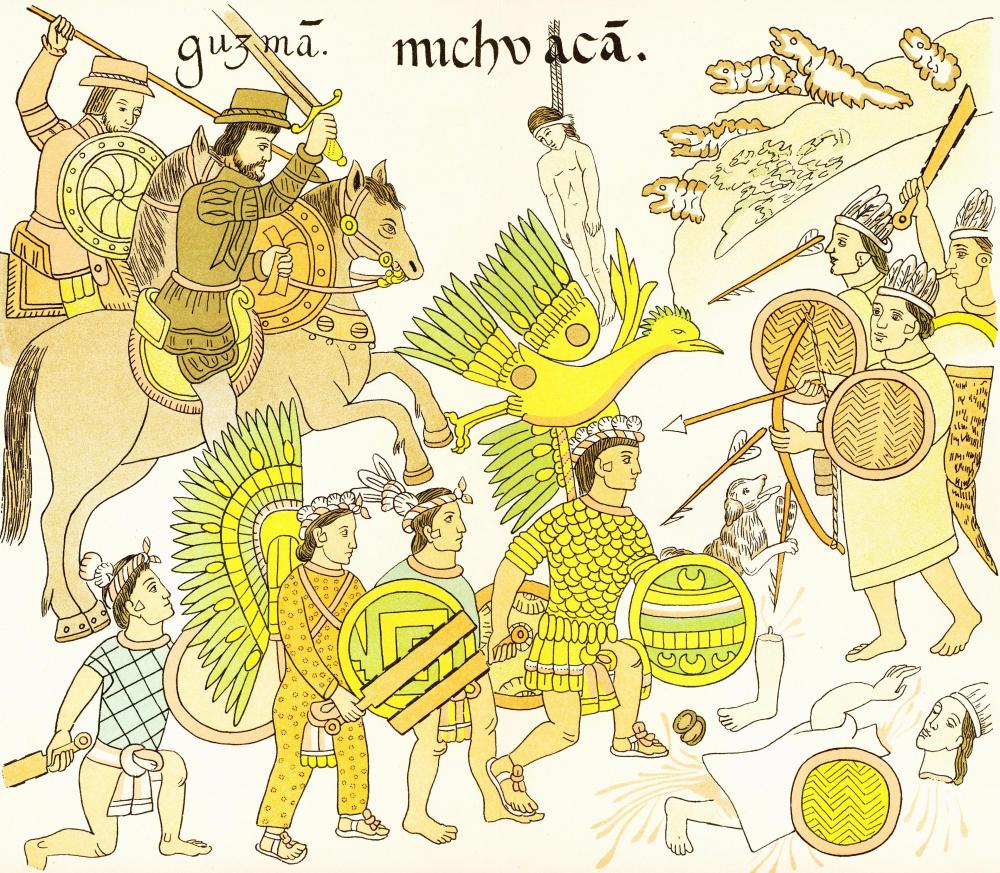

The Spanish relied on Indigenous allies. The Tlaxcala were among the most of import Spanish allies in their conquest. This sixteenth-century drawing depicts the Spanish and their Tlaxcalan allies fighting against the Purépecha. Wikimedia.

Farther southward, forth the Andes Mountains in South America, the Quechuas, or Incas, managed a vast mountain empire. From their uppercase of Cuzco in the Andean highlands, through conquest and negotiation, the Incas built an empire that stretched around the western one-half of the South American continent from nowadays day Republic of ecuador to central Republic of chile and Argentina. They cutting terraces into the sides of mountains to farm fertile soil, and by the 1400s they managed a thousand miles of Andean roads that tied together perhaps twelve million people. But like the Aztecs, unrest betwixt the Incas and conquered groups created tensions and left the empire vulnerable to invaders. Smallpox spread in advance of Spanish conquerors and hit the Incan empire in 1525. Epidemics ravaged the population, cutting the empire's population in half and killing the Incan emperor Huayna Capac and many members of his family. A bloody state of war of succession ensued. Inspired past Cortés's conquest of Mexico, Francisco Pizarro moved south and found an empire torn past chaos. With 168 men, he deceived Incan rulers, took command of the empire, and seized the capital city, Cuzco, in 1533. Disease, conquest, and slavery ravaged the remnants of the Incan empire.

Subsequently the conquests of United mexican states and Peru, Spain settled into its new empire. A vast administrative hierarchy governed the new holdings: regal appointees oversaw an enormous territory of landed estates, and Ethnic laborers and administrators regulated the extraction of aureate and silver and oversaw their transport across the Atlantic in Castilian galleons. Meanwhile, Spanish migrants poured into the New Globe. During the sixteenth century alone, 225,000 migrated, and 750,000 came during the entire three centuries of Castilian colonial rule. Spaniards, often single, immature, and male, emigrated for the various promises of land, wealth, and social advancement. Laborers, craftsmen, soldiers, clerks, and priests all crossed the Atlantic in large numbers. Indigenous people, still, always outnumbered the Castilian, and the Spaniards, past both necessity and blueprint, incorporated Native Americans into colonial life. This incorporation did not mean equality, however.

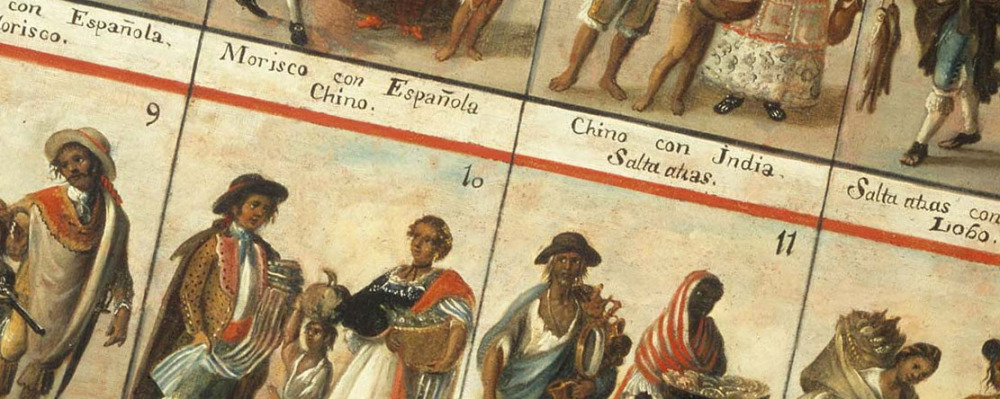

An elaborate racial hierarchy marked Spanish life in the New World. Regularized in the mid-1600s but rooted in medieval practices, the Sistema de Castas organized individuals into various racial groups based on their supposed "purity of claret." Elaborate classifications became almost prerequisites for social and political advocacy in Spanish colonial society. Peninsulares—Iberian-born Spaniards, or españoles—occupied the highest levels of administration and caused the greatest estates. Their descendants, New World-born Spaniards, or criollos, occupied the next rung and rivaled the peninsulares for wealth and opportunity. Mestizos—a term used to describe those of mixed Spanish and Ethnic heritage—followed.

Casta paintings illustrated the varying degrees of intermixture between colonial subjects, defining them for Spanish officials. Unknown artist, Las Castas, Museo Nacional del Virreinato, Tepotzotlan, Mexico. Wikimedia.

Like the French later on in North America, the Spanish tolerated and sometimes even supported interracial matrimony. There were simply also few Spanish women in the New Earth to back up the natural growth of a purely Castilian population. The Cosmic Church endorsed interracial marriage every bit a moral bulwark against bastardy and rape. By 1600, mestizos made up a large portion of the colonial population.32 By the early 1700s, more than than ane third of all marriages bridged the Spanish-Ethnic divide. Separated by wealth and influence from the peninsulares and criollos, mestizos typically occupied a middling social position in Spanish New World guild. They were not quite Indios, or Indigenous people, but their lack of limpieza de sangre, or "pure blood," removed them from the privileges of full-blooded Spaniards. Spanish fathers of sufficient wealth and influence might shield their mestizo children from racial prejudice, and a number of wealthy mestizos married españoles to "whiten" their family unit lines, but more oft mestizos were bars to a middle station in the Spanish New World. Enslaved and Indigenous people occupied the lowest rungs of the social ladder.

Many manipulated the Sistema de Castas to gain advantages for themselves and their children. Mestizo mothers, for instance, might insist that their mestizo daughters were actually castizas, or quarter-Indigenous, who, if they married a Spaniard, could, in the eyes of the police, produce "pure" criollo children entitled to the total rights and opportunities of Spanish citizens. Simply "passing" was an option only for the few. Instead, the massive Native populations within Spain'south New World Empire ensured a level of cultural and racial mixture—or mestizaje—unparalleled in British Due north America. Spanish N America wrought a hybrid culture that was neither fully Spanish nor fully Indigenous. The Spanish not only built Mexico Metropolis atop Tenochtitlán, but food, linguistic communication, and families were too synthetic on Indigenous foundations. In 1531, a poor Indigenous named Juan Diego reported that he was visited by the Virgin Mary, who came as a dark-skinned Nahuatl-speaking Ethnic woman.33 Reports of miracles spread across Mexico and the Virgen de Guadalupe became a national icon for a new mestizo society.

Our Lady of Guadalupe is maybe the most culturally important and extensively reproduced Mexican-Catholic image. In the iconic depiction, Mary stands atop the tilma (peasant cloak) of Juan Diego, on which according to his story appeared the prototype of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Throughout Mexican history, the story and image of Our Lady of Guadalupe has been a unifying national symbol. Mexican retablo of Our Lady of Guadalupe, 19th century, in El Paso Museum of Art. Wikimedia.

From Mexico, Spain expanded northward. Lured by the promises of gilt and another Tenochtitlán, Spanish expeditions scoured N America for another wealthy Indigenous empire. Huge expeditions, resembling vast moving communities, composed of hundreds of soldiers, settlers, priests, and enslaved people, with enormous numbers of livestock, moved beyond the continent. Juan Ponce de León, the conqueror of Puerto Rico, landed in Florida in 1513 in search of wealth and enslaved laborers. Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca joined the Narváez expedition to Florida a decade later just was shipwrecked and forced to embark on a remarkable multiyear odyssey along the declension of the Gulf of United mexican states and Texas into Mexico. Pedro Menéndez de Avilés founded St. Augustine, Florida, in 1565, and information technology remains the oldest continuously occupied European settlement in the present-day Usa.

But without the rich golden and silver mines of Mexico, the plantation-friendly climate of the Caribbean, or the exploitive potential of large Indigenous empires, North America offered little incentive for Spanish officials. Nevertheless, Spanish expeditions combed North America. Francisco Vázquez de Coronado pillaged his way across the Southwest. Hernando de Soto tortured and raped and enslaved his fashion across the Southeast. Soon Espana had footholds—however tenuous—beyond much of the continent.

V. Decision

The "discovery" of America unleashed horrors. Europeans embarked on a debauching path of death and destructive exploitation that wrought murder and greed and slavery. Simply affliction was deadlier than whatever weapon in the European armory. It unleashed death on a scale never before seen in human history. Estimates of the population of pre-Columbian America range wildly. Some debate for every bit much as 100 meg, some as low as 2 million. In 1983, Henry Dobyns put the number at 18 million. Whatever the precise estimates, nigh all scholars tell of the utter devastation wrought past European disease. Dobyns estimated that in the get-go 130 years following European contact, 95 pct of Native Americans perished.34 (At its worst, Europe's Black Decease peaked at expiry rates of 35 percent. Nothing else in history rivals the American demographic disaster.) A x-one thousand-year history of disease striking the New World in an instant. Smallpox, typhus, bubonic plague, influenza, mumps, measles: pandemics ravaged populations up and downwardly the continents. Wave later on wave of affliction crashed relentlessly. Affliction flung whole communities into chaos. Others it destroyed completely.

Illness was only the virtually terrible in a cantankerous-hemispheric exchange of violence, civilization, merchandise, and peoples—the so-called Columbian Exchange—that followed in Columbus's wake. Global diets, for instance, were transformed. The Americas' calorie-rich crops revolutionized Sometime World agriculture and spawned a worldwide population smash. Many modern associations between food and geography are by products of the Columbian Substitution: potatoes in Ireland, tomatoes in Italian republic, chocolate in Switzerland, peppers in Thailand, and oranges in Florida are all manifestations of the new global exchange. Europeans, for their role, introduced their domesticated animals to the New World. Pigs ran rampant through the Americas, transforming the mural as they spread throughout both continents. Horses spread equally well, transforming the Native American cultures who adapted to the newly introduced animal. Partly from trade, partly from the remnants of failed European expeditions, and partly from theft, Indigenous people caused horses and transformed Native American life in the vast North American plains.

The Europeans' arrival bridged two worlds and 10 one thousand years of history largely separated from each other since the closing of the Bering Strait. Both sides of the world had been transformed. And neither would ever again exist the aforementioned.

VI. Primary Sources

i. Native American creation stories

These two Native American creation stories are among thousands of accounts for the origins of the world. The Salinian and Cherokee, from what we at present call California and the American southeast respectively, both exhibit the common Native American tendency to locate spiritual power in the natural globe. For both Native Americans and Europeans, the collision of two continents challenged old ideas and created new ones besides.

2. Journal of Christopher Columbus, 1492

First encounters between Europeans and Native Americans were dramatic events. In this account, we see the assumptions and intentions of Christopher Columbus, as he immediately began assessing the potential of these people to serve European economic interests. He also predicted like shooting fish in a barrel success for missionaries seeking to convert these people to Christianity.

3. An Aztec business relationship of the Spanish attack

This source aggregates a number of early written reports by Aztec authors describing the destruction of Tenochtitlan at the easily of a coalition of Spanish and Indigenous armies. This collection of sources was assembled by Miguel Leon Portilla, a Mexican anthropologist.

4. Bartolomé de las Casas describes the exploitation of Ethnic people, 1542

Bartolomé de Las Casas, a Spanish Dominican priest, wrote directly to the Male monarch of Espana hoping for new laws to prevent the cruel exploitation of Native Americans. Las Casas'due south writings chop-chop spread around Europe and were used every bit humanitarian justification for other European nations to challenge Spain's colonial empire with their own schemes of conquest and colonization.

5. Thomas Morton reflects on Native Americans in New England, 1637

Thomas Morton both admired and condemned aspects of Native American civilization. In his descriptions, we can find not only information about the people he is describing but also a window into the concerns of Englishmen like Morton who could use descriptions of Native Americans as a means of criticizing English culture.

6. The story of the Virgin of Guadalupe

Cuauhtlatoatzin was one of the get-go Aztec men to convert to Christianity after the Spanish invasion. Renamed equally Juan Diego, he soon thereafter reported an advent of the Virgin Mary chosen the Virgin of Guadalupe. This bogeyman became an of import symbol for a new native Christianity. These excerpts are translated from an business relationship first published in Nahuatl by Luis Lasso de la Vega in 1649.

7. Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca travels through North America, 1542

Spanish explorer, Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, traveled beyond the Gulf South, from Florida to Mexico. As he traveled, Cabeza de Vaca developed a reputation as a religion healer. In his business relationship he claimed several instances of performing miracles, illustrating his spiritual beliefs also as offer a rare, if possibly unreliable, glimpse at the life of Native Americans in the surface area.

8. Photograph of Cliff Palace

Native peoples in the Southwest began amalgam these highly defensible cliff dwellings in 1190 CE and continued expanding and refurbishing them until 1260 CE before abandoning them around 1300 CE. Irresolute climatic atmospheric condition resulted in an increased competition for resources that led some groups to ally with their neighbors for both protection and subsistence. The circular rooms in the foreground were chosen kivas and had ceremonial and religious importance for the inhabitants. Cliff Palace had 23 kivas and 150 rooms housing a population of approximately 100 people; the number of rooms and big population has led scholars to believe that this complex may have been the centre of a larger polity that included surrounding communities.

9. Casta painting

The elaborate Sistema de Castas revealed ane of the less-discussed effects of Spanish conquest: sexual liaisons and their progeny. Casta paintings illustrated the varying degrees of intermixture between colonial subjects, defining them for Spanish officials. Race was less fixed in the Castilian colonies, as some individuals, through legal action or colonial service, "changed" their race in the colonial records. Though this particular prototype does non, some casta paintings attributed particular behaviors to different groups, demonstrating how class and race were intertwined.

VII. Reference Textile

This affiliate was edited by Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, with content contributions past L. D. Burnett, Michelle Cassidy, Kathryn Green, D. Andrew Johnson, Joseph Locke, Dawn Marsh, Christen Mucher, Cameron Shriver, Ben Wright, and Garrett Wright.

Recommended citation: Fifty. D. Burnett et al., "The New World," in The American Yawp, eds. Joseph Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018).

Recommended Reading

- Alt, Susan, ed. Ancient Complexities: New Perspectives in Pre-Columbian N America. Salt Lake Urban center: University of Utah Press, 2010.

- Bruhns, Karen Olsen. Ancient Southward America. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Claasen, Cheryl, and Rosemary A. Joyce, eds. Women in Prehistory: Northward America and Mesoamerica. Philadelphia: Academy of Pennsylvania Press, 1994.

- Melt, Noble David. Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492–1650. New York: Cambridge Academy Press, 1998.

- Crosby, Alfred West. The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492. New York: Praeger, 2003.

- Dewar, Elaine. Bones. Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2001.

- Dye, David. State of war Paths, Peace Paths: An Archæology of Cooperation and Conflict in Native Eastern North America. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press, 2009.

- Fenn, Elizabeth A. Encounters at the Eye of the World: A History of the Mandan People. New York: Loma and Wang, 2014.

- Jablonski, Nina Yard. The First Americans: The Pleistocene Colonization of the New World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

- John, Elizabeth A. H. Storms Brewed in Other Men's Worlds: The Confrontation of Indians, Spanish, and French in the Southwest, 1540–1795, 2d ed. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996.

- Kehoe, Alice Brook. America Before the European Invasions. New York: Routledge, 2002.

- Leon-Portilla, Miguel. The Cleaved Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico. Boston: Beacon Books, 1992.

- Mann, Charles C. 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. New York: Vintage Books, 2006.

- Meltzer, David J. Showtime Peoples in a New World: Colonizing Ice Age America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

- Mt. Pleasant, Jane. "A New Paradigm for Pre-Columbian Agriculture in N America." Early American Studies 13, no. 2 (Bound 2015): 374–412.

- Oswalt, Wendell H. This Land Was Theirs: A Study of Native N Americans. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Pauketat, Timothy R. Cahokia: Ancient America'due south Great City on the Mississippi. New York: Penguin, 2010.

- Pringle, Heather. In Search of Ancient Due north America: An Archaeological Journey to Forgotten Cultures. New York: Wiley, 1996.

- Reséndez, Andrés. A Land So Strange: The Epic Journey of Cabeza de Vaca. New York: Bones Books, 2009.

- Restall, Matthew. Seven Myths of the Castilian Conquest. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Scarry, C. Margaret. Foraging and Farming in the Eastern Woodlands. Gainesville: University Printing of Florida, 1993.

- Schwartz, Stuart B. Victors and Vanquished: Spanish and Nahua Views of the Conquest of Mexico. New York: Bedford St. Martin's, 2000.

- Seed, Patricia. Ceremonies of Possession: Europe's Conquest of the New Earth, 1492–1640. New York: Cambridge Academy Press, 1995.

- Townsend, Camilla. Malintzin's Choices: An Indian Woman in the Conquest of United mexican states. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Printing, 2006.

- Weatherford, Jack. Indian Givers: How the Indians of the Americas Transformed the Earth. New York: Random Firm, 1988.

Notes

- A. L. Kroeber, ed., University of California Publications: American Archaeology and Ethnology, Vol. x (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1911–1914), 191–192. [↩]

- James F. Barnett Jr., Mississippi'southward American Indians (Jackson: Academy Printing of Mississippi, 2012), 90. [↩]

- Edward Westward. Osowski, Indigenous Miracles: Nahua Authority in Colonial Mexico (Tucson: Academy of Arizona Press, 2010), 25. [↩]

- David J. Meltzer, First Peoples in a New Earth: Colonizing Ice Age America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), 170. [↩]

- Knut R. Fladmark, "Routes: Alternating Migration Corridors for Early Human being in North America," American Antiquity 44, no. ane (1979): 55–69. [↩]

- Jessi J. Halligan et al., "Pre-Clovis Occupation 14,550 Years Ago at the Page-Ladson Site, Florida, and the People of the Americas," Science Advances two, no. five (May 13, 2016) and Michael R. Waters et al, "The Buttermilk Creek Circuitous and the Origins of Clovis at the Debra L. Friedkin Site, Texas," Science 331 (March 25, 2011), 1599-1603. [↩]

- Tom D. Dillehay, The Settlement of the Americas: A New Prehistory (New York: Bones Books, 2000). [↩]

- Richard A. Diehl, The Olmecs: America's First Civilization (London: Thames and Hudson, 2004), 25. [↩]

- Jane Mt. Pleasant, "A New Paradigm for Pre-Columbian Agriculture in North America," Early American Studies 13, no. 2 (Spring 2015): 374–412. [↩]

- Richard H. Steckel, "Wellness and Nutrition in Pre-Columbian America: The Skeletal Evidence," Journal of Interdisciplinary History 36, no. 1 (Summertime 2005): xix–21. [↩]

- Traci Ardren, "Studies of Gender in the Prehispanic Americas," Periodical of Archaeological Research Vol. 16, No. 1 (March 2008), 1-35. [↩]

- Elizabeth Colina Boone and Walter D. Mignolo, eds., Writing Without Words: Alternative Literacies in Mesoamerica and the Andes (Durham, NC: Duke Academy Printing, 1994). [↩]

- Stuart J. Fiedel, Prehistory of the Americas (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 217. [↩]

- H. Wolcott Price, "Making and Breaking Pots in the Chaco Earth," American Antiquity 66, no. 1 (January 2001): 65. [↩]

- Anna Sofaer, "The Chief Architecture of the Chacoan Culture: A Cosmological Expression," in Anasazi Architecture and American Pattern, ed. Baker H. Morrow and 5. B. Price (Albuquerque: Academy of New Mexico Press, 1997). [↩]

- Timothy R. Pauketat and Thomas E. Emerson, eds., Cahokia: Domination and Ideology in the Mississippian World (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997), 31. [↩]

- Thomas E. Emerson, "An Introduction to Cahokia 2002: Diversity, Complexity, and History," Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 27, no. 2 (Fall 2002): 137–139. [↩]

- Amy Schutt, Peoples of the River Valleys: The Odyssey of the Delaware Indians (Philadelphia: Academy of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), 7–30. [↩]

- Erna Gunther, "An Analysis of the First Salmon Ceremony," American Anthropologist 28, no. 4 (October–December 1926): 605–617. [↩]

- Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Vol. vi (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983), https://world wide web.loc.gov/exhibits/lewisandclark/transcript68.html. [↩]

- Coll Thrush, Native Seattle: Histories from the Crossing-Over Place, 2d ed. (Seattle: University of Washington Printing, 2007), 126. [↩]

- Walter Rodney, A History of the Upper Guinea Co (Monthly Review Press, 1970); Ivor Wilks, "State, labour, capital and the forest kingdoms of Asante: a model of early change," In The Evolution of Social Systems, Edited by J. F. Friedman and M. J. Rowlands. London: Duckworth, 1977): , pp. 487-534 ; Walter Rodney, "Gold and Slaves on the Gilded Declension," Transactions of the Historical Social club of Ghana 10 (1969) 13-28; Alan F. C. Ryder, Republic of benin and The Europeans, 1485-1897 (London: Longman, 1969); John Thornton, "Early Kongo-Portuguese Relations, 1483-1575: A New Interpretation" History in Africa 8 (1981): 183-204. French translation in Cahiers des Anneaux de la Mémoire 3 (2001); "The Portuguese in Africa," in Francisco Bethencourt and Diogo Ramada Curto, eds. Portuguese Oceanic Expansion, 1400-1800 (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Printing, 2007), pp. 138-160; and Linda Heywood, "Slavery and its Transformation in the Kingdom of Kongo: 1491-1800," Periodical of African History, 50 (2009):1-22. [↩]

- Joseph C. Miller, The Problem of Slavery as History: A Global Arroyo (New Haven: Yale University Printing, 2012). [↩]

- Clements R. Markham, ed. and trans., The Journal of Christopher Columbus (During His First Voyage), and Documents Relating to the Voyages of John Cabot and Gaspar Corte Real (London: Hakluyt Society, 1893), 73, 135, 41. [↩]

- Bartolomé de Las Casas, A Brief Account of the Devastation of the Indies . . . (1552; Projection Gutenberg, 2007), 147. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/20321, accessed June 11, 2018. [↩]

- Dean R. Snow, "Microchronology and Demographic Bear witness Relating to the Size of Pre-Columbian North American Indian Populations," Scientific discipline 268, no. 5217 (June 16, 1995): 1601. [↩]

- Jack Weatherford, Indian Givers: How the Indians of the Americas Transformed the World (New York: Random House, 1988), 195. [↩]

- J. H. Elliott, Regal Spain 1469–1716 (London: Edward Arnold, 1963), 53. [↩]

- Victor Butler-Thomas et al, The Cambridge Economic History of Latin America: Volume 1, The Colonial Era and the Short Nineteenth Century (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005). [↩]

- Bernal Díaz del Castillo, The Discovery and Conquest of United mexican states, 1517–1521, trans. A. P. Maudslay (New York: Da Capo Press, 1996), 190–191. [↩]

- Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: Full general History of the Things of New Espana (Table salt Lake Metropolis: Academy of Utah Press, 1970). [↩]

- Suzanne Bost, Mulattas and Mestizas: Representing Mixed Identities in the Americas, 1850–2000 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2003), 27. [↩]

- Stafford Poole, C. Grand., Our Lady of Guadalupe: The Origins and Sources of a Mexican National Symbol, 1531–1797 (Tucson: University of Arizona Printing, 1995). [↩]

- Henry F. Dobyns, Their Number Become Thinned: Native American Population Dynamics in Eastern Due north America (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1983). [↩]

Source: http://www.americanyawp.com/text/01-the-new-world/

0 Response to "1300 Foot Long Earthen Mound in Ohio Gotypes of Art Most Liekly Produced in the Northwest Coast"

Post a Comment